Understanding Neurodevelopmental Conditions in Adopted and Fostered Young People

Online Webinar

Wednesday 13 August 2025

20:00-21:00

Over 130 parents and professionals attended the talk presented by Dr Tom Cawthorne and Dr Matt Woolgar

About the Event

-

Led by Dr Matt Woolgar & Tom Cawthorne, who are leading experts in the mental health of adopted and fostered young people, the session explored:

How can we diagnose autism and ADHD in adopted or fostered young people, including those with attachment difficulties or early life trauma?

Why are the rates of neurodevelopmental conditions higher in adopted and fostered children than in the general population?

How can families access specialist neurodevelopmental assessment?

How can we adapt interventions for young people with neurodevelopmental differences?

Plus, there will be time to answer any questions that you may have throughout the session.

-

Ideal for:

Adoptive parents and foster carers

Special guardians and kinship carers

Social workers, educators, and mental health professionals

Anyone supporting adopted or fostered young people who may have unmet neurodevelopmental needs

-

Understanding neurodevelopmental conditions in adopted and fostered children can be life-changing. With the right knowledge, families and professionals can access earlier diagnoses, tailor interventions, and offer children the consistent, evidence-based support they need to thrive.

There will also be time throughout the session for you to ask questions and share reflections.

-

Dr Matt Woolgar is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist in the National Adoption & Fostering Clinic, based at the Maudsley Hospital, London. He is also an academic at King’s College London, focusing on attachment, parenting, and developmental psychopathology. Matt has a particular interest in the assessment and treatment of complex presentations in adopted children or children from the care system, especially with regard to disentangling the effects of biological and neurodevelopmental factors from attachment, trauma, and behavioural issues.

Dr Tom Cawthorne was the Senior Clinical Psychologist in the National Adoption & Fostering Clinic and is currently undertaking a research fellowship focused on improving mental health care for adopted and fostered young people. He has a specialist interest in supporting children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental differences, including autism and ADHD. Tom brings extensive experience in conducting neurodevelopmental assessments to inform diagnosis and in delivering tailored psychological interventions for the co-occurring mental health challenges often faced by this group. This includes supporting young people with neurodevelopmental conditions who have experienced significant trauma and attachment disruptions.

Questions & Answers

There were so many interesting questions and comments raised in the chat during our webinar that we didn’t have time to address them all. We have therefore reviewed the chat, drawn out the main themes, and offered some responses below. These may not be definitive answers, and not everyone will agree, but where possible we have included supporting evidence.

-

Much of what we have written here relates to services funded by the adoption support fund and then by the adoption and special guardianship support fund in England [provided by the Department for Education, and administered by an engineering and infrastructure private limited company] and we are completely aware that these opportunities [and the problems that come with them] do not operate in the same way in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, or internationally. However, some of the principles are also seen in other areas, so we hope that the answers below are still helpful for people outside of England.

At the Child Wellbeing Clinic, we provide support for young people and their families from across the United Kingdom and internationally. If you are unable to access the ASF, our services can be self-funded. In some cases, support may also be covered by health insurance or, on rare occasions, by the local authority.

If you have any questions about accessing specialist support through our service, please contact us at info@cwclinic.com

-

“The overlap between ACE’s ASC ADHD and FASD seems beyond CAMHs and any SW”

ACEs refers to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs); ASC to Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC); ADHD to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); FASD to Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD); CAMHS to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS); and SW to social worker (SW).

To be fair it is quite complicated and to explore these effectively you do need a lot of “content knowledge” of different areas as well as of the research on the way that these features intersect and interact, plus professional knowledge on differential diagnosis. Matt edited a collection of articles on the diverse neurobiological consequences of early adversity for practitioners [ link ] but a) this was just some of the complexity and b) even though the scientists did their best to be accessible, it was still pretty complex in places. As an aside, most of these are or were UK based world experts, but despite the UK’s enormous world leading scientific knowledge in the area these researchers rarely seem to get asked into the UK adoption policy world. Odd, to say the very least. Maybe that will change [ link ].

Alternatively, there is a scientific framework that most of us in research work to called developmental psychopathology [DP] and it can be pretty simple to understand (Matt wrote a blog on it - [ link ]. Basically, people are individuals and life is complex (it is a bit more complex than that, tbh, but definitely not so simple as “if you are adopted then you always have X or Y” (where X,Y are a top down homogenising category, such as attachment, trauma etc etc or indeed whatever over-simplification is currently in fashion). Such a simplistic approach flouts the central principle of multifinality (i.e., a given type of experience can evoke a wide range of outcomes, not just one or two - [link], and over-simplistic approaches are also just not consistent with common sense or lived experience.

For more information about the assessment and intervention packages offered by our specialist clinicians, please contact info@cwclinic.com

-

That needs a lot of unpacking. But perhaps part of it is a naivety about attachment & trauma, and the role of love, as if love were enough to cure all. Love is great, of course: probably necessary, but rarely sufficient - for very good, clear reasons in the context of complexity. And when a child is complex it overwhelms the systems around them - one parent put in the chat that CAMHS had said they had hoped not to have to assess their child… an honest response, maybe, but not in any way okay. To be fair, I do understand that, if a pressured system, pushed to bursting point has to take on exceptional cases the system will struggle. But that only considers the system and not the child or their family. But, as several of you asked, who then does take on these cases? Ultimately, if a professional feels they can't cope with this complexity, then you've got an easy explanation of locating the issues in the parents [birth or adoptive].

In our old national NHS clinic, would see families where there could indeed have been things parents could have done differently, but many were in no position to begin to try doing things differently because they'd not had the right help, support and had been blamed and felt harassed for too long. Then a family can edge towards a self-fulfilling prophecy, so an external service can look in at the family and claim it is the ‘family’s fault’… and it gets complicated. That is, if a professional starts observing a family system when a child is, say, 12 years old, then they will not have seen the evolution of problems up to that point, but only see how the family is coping at this point, and may think that the parents are “doing it all wrong” rather than seeing how this current state of crisis has emerged over time in the absence of effective help and support. If that makes sense? But even so, it really ought to be the practitioner's job to do the thinking about the developmental processes that have led to the here and now issues for the family and avoid blame.

-

To diagnose one thing [i.e., disorder], you need good content knowledge of that thing – i.e., what it is and what it is not. And there are many practitioners who are good at doing that for one or two things - in the NHS there are typically specialisms across different ‘care pathways’ where clinicians become very good at the one or two things that their care pathway is organised around [e.g., neurodevelopmental vs psychosis vs eating disorders etc]. It becomes more difficult when there are several possible conditions in play, which may not be part of that core content knowledge set. It is possible to be able to do all this – in our former NHS service, the National Adoption & Fostering Clinic, we could all of us assess anything - but running a team with that much content knowledge is expensive and difficult for service managers to tolerate in a streamlined service offer – and obviously our service was closed for being too expensive [for the ASF who became our main funder].

There are so many financial pressures to avoid an open and inclusive approach to assessments, and the Adoption Support Fund has massively contributed to that pressure by an unevidenced and wholly arbitrary restriction of problems to “attachment and trauma” which prevents open ended assessments being funded, which is definitely a problem, but which has also distorted the narratives around adoption. That means you may well get an expert who can look and see whether your child has or has not got ADHD, but then faced with a wider range of problems they will be under enormous pressure to say that in fact it is attachment or trauma, or some other top down, homogenising oversimplification only because the child is adopted; or to say yes it is ADHD, but most of the problems are actually to do with attachment and trauma etc, so you need to go to a non-NHS adoption supprt provider, rather than consider, for example, co-occurring depression, anxiety or some other issues. There typically isn't the service capacity to think what else might be going on. Obviously, some clinicians are willing and able to do that, but they will be probably fighting against massive external pressures to avoid doing it.

So the ability to diagnose different issues effectively isn't just about a specific profession, or their training, or if they are in private or NHS services - it can often be a bit of good or bad fortune who you get, and what they can do.

-

The fact that there were lots of questions about FASD is interesting. And that's a feature we have noticed become more prominent in the adoption world in the last 5 years or so. That is interesting in itself, but having been in the sector for over 20 years, there are often waves of newish thinking that come in to fashion and then go out again – not vanishing entirely, but settling into the mix with all the other previous new ways. Maybe this is part of that? There does seem to be a desire to find one thing that explains it all, and, while we are loath to get into a pros and cons debate on FASD specifically, the evidence is very clear that lots of things have different kinds of effects, in different young people, with wildly different early histories and that diversity and difference is the key [as per developmental psychopathology and the ideas of equi- and multi- finality]. And if you accept that, then while it may well be helpful to consider a primary aetiological factor, often there will be lots of other things contributing, some of which are unknown, and there is often the difficult task of having to cope with that uncertainty. Almost certainly, that is a stance that will annoy quite a few people. That is not to say that a specific aetiological factor, such as foetal toxins, are trivial, because that would be silly and inconsistent with the evidence – and there are many cases where they are central - but it is also crucial to highlight that human development is always complex and many things contribute to it, so as long as you keep an open mind to all the possibilities, then you are much more likely to end up with the best possible formulation of an individual child's needs. But, as above, to do that is expensive and complicated, and many services can't bear to think about all that, especially when they can choose one thing that hopes to explain it all.

So we are a bit loath to give a brief overview here – not least because there are lots of resources already. But also because some of the narratives we have encountered seem to offer up FASD as primary to everything else and over-riding everything else, and that doesn't seem consistent with the evidence. It can be very important, but nothing explains everything, really. So, while we will do a webinar in the future on foetal toxins, it won't be to highlight everything that FASD has been correlated with, but to set it all within a broader context of risk and outcomes. That may or may not be to your taste…

A future webinar on foetal toxins will place FASD within a broader context of risk and outcomes. Please contact info@cwclinic.com if you would like information about our future webinars.

-

For many reasons, but the biggest is probably that on average (but not always, so not at all deterministically) parents of care experienced children often have their own highly heritable neurodivergences. You can often find hints of this in the birth family reports…. But not always, because people growing up in the social disadvantage characteristic of birth families get reduced access to mental health and educational assessments and support – so their needs are never recognised as children and then as adults their lives are complicated and the parenting tasks potentially overwhelming. Their difficulties are undiagnosed in their own lives and remain invisible in the birth family record. That is probably the biggest factor, but it is difficult to quantify, and there are surely others. But it does seem grossly naive to think it could all be down to experience rather than the interaction between intrinsic factors [e.g., genetics] and experiences. We wrote about some of these issues in a recent Health Notes [ link ].

-

How long families have to wait in the NHS varies massively. One service, not in London, was telling people the wait was “over 3 years” for an autism assessment, which was true because it was estimated to be nearer 10, which was indeed more than 3 years, but…?? In other places it could be under a year. Hugely variable. Sometimes you can use the ‘Right to Choose’ providers [private providers accessed via the NHS] but even some of these are beginning to get significant wait lists. That is something to discuss with your GP.

However, sometimes for adoptive families, and care experienced children more generally, the issue is how to get on the wait list in the first place, even before you consider how long that wait list is, because as noted above, it can be very tempting to ascribe all or most of a young person's difficulties to their adoption; to “attachment and trauma”; or to whatever is currently fashionable in the sector - or more specifically what is currently fashionable in that area of the country in the sector, because having worked in the national clinic, we frequently saw how children with very similar issues were understood very differently in different parts of the country, depending on what particular, typically unevidenced, model they had recently bought into to ‘explain’ everything about adoption. This is something that the DfE’s own research on the impact of the ASGSF has demonstrated that adopters have reported.

At the Child Wellbeing Clinic we are able to provide specialist assessments, including for autism and ADHD. All our assessments are completed by highly experienced clinicians and use the gold-standard assessment tools. We can typically offer an assessment appointment within 2 weeks from the point of referral. Please contact info@cwclinic.com if you would like further information.

-

It is interesting to think about consent and how that operates for adoption. Of course, the adoptive family holds consent, but access to funded services via the ASGSF is in the hands of social workers - but access to health and education support is also routinely in the hands of various other professionals not parents, so that in itself is not atypical.

Our own view, and it is apparently quite controversial, is that access to mental health services ought to be guided by mental health assessments, conducted by mental health experts, funded, overseen and quality assured by mental health services, rather than by professionals whose primary skill set, and it is a very important skill set, is definitely not mental health assessment [nor that these assessments should then evaluated by an engineering & infrastructure company and ultimately funded by an Education Department– see our recent letter about this [link]. In a similar way, while we may think we are pretty great at our jobs as mental health experts, we also have enough insight to recognise that we would likely be hopeless social workers, terrible teachers and probably useless at many other jobs, because we don't have the basic training, let alone advance practice knowledge, in those professional areas… But that is apparently a peculiar belief.

-

We discussed this briefly in the webinar. Essentially, we recognise that this is a term people like, we recognise that people who are using it are describing a constellation of behaviours that are meaningful and important, but we also think that it covers more than one type of presentation and/or cause, and therefore may need more than one broad type of response, which should be adapted and fitted to the individual child & family. So we don't tend to use the term [and it isn’t a recognised diagnosis for some of the reasons we just highlighted] but we would definitely work with it as part of the formulation, and also definitely not discount it as a helpful description and would also want to know what a family had found helpful about it.

Please contact info@cwclinic.com if you would like more information about our assessment and intervention packages, including for young people with PDA profiles.

-

The prognosis for autism is that it is a lifelong condition, but that its impact and the effective adaptations may well vary significantly over development. It is not going to just go away or be cured by parental love & attention etc, but if a person finds a niche that works for them, then development can be an opportunity for neuroaffirmative growth and wellbeing. On the other hand, if the task demands of development increase for an individual in their niche, then life could become harder and more stressful.

It is different for ADHD. 20 years ago, the story was that that ADHD typically “burns out” by early adulthood. Then that idea was revised down to about 50% and now estimates can be as high as 75% as still impaired. But again, we need to think about what persistence means. And the criteria for what constitutes ADHD have changed a bit over the years which means persistence can be hard to determine. Probably many symptoms do still hang around for most people affected as children, but the extent to which these impact on their life in meaningful ways may vary significantly according to life challenges and how their development progressed. It is also perhaps worth drawing a distinction between the significantly impaired and those who have milder difficulties – but that’s an interesting debate in its own right and not everyone would agree. Whatever else, as a 5yr old develops their attention & concentration will also develop, and that is true for a child with or without ADHD, but if problems with ADHD persist then the development of their skills in these domains will remain lower than for their peers. But task demands and expectations are also increasing at different rates across different domains – so it is hard to predict a child’s future adaptation. It is rare a child stays where they are in terms of attention and concentration skills, unless there is something else going on, such as intellectual disability that is acting as a brake on the broader developmental process.

-

Tricky – if only we knew, then our national clinic might have survived… There is a [false] belief that:

a) there is no evidence base that applies to adopted children (no, they are still children, and there is no evidence to suggest that the evidence doesn't apply to them…)

b) that the alternative approaches often used with adopted children have evidence - but that is typically a misunderstanding of what evidence is and what it isn't; for example, we have heard commissioners say “if it didn’t have an evidence base, the ASF wouldn’t have funded it!” [in press], which is plainly wrong, and even for someone with a fairly limited understanding of, or interest in science, should have been easy to have ascertained as false.

But what we should all be doing, in all our treatments, is to be clear what the treatment is for [the presenting issue], what the goals of that treatment are and how the treatment is progressing in relation to those goals. This is just very basic good clinical practice and how the NHS and their delivery partners should have been organising CYP mental health and well-being practice for the last 15 years. And we can make a further distinction between “evidence-based practice” and “practice-based evidence”, which may sound like the same thing, but isn't quite. Essentially the latter means that you can try things that don't currently have an evidence base, and indeed they may well work for a specific child, but what you ought to do is provide evidence for that clinical practice with that specific child, by being clear about collaboratively established goals, and tracking progress towards those goals. So I would recommend you all insist on that approach for your child's treatment, whether or not an evidence-based approach is undertaken. Unfortunately, what the Adoption Support Fund in England did, is come up with four eclectic [almost random] outcome measures, which were probably decided by a closed committee in an oak panelled room deep in Westminster, but without really engaging with the facts of good clinical practice. So you may get some outcome measures, but the most important ones for you to focus in on are probably the goal-based outcomes [GBOs], which have been collaboratively agreed, and which you can track over time, indicating progress towards the things that you really want to see achieved. If something is working and going in the right direction for you and your child, you probably don't really care whether or not it has got three dozen randomized control trials [RCTs] behind it to support its use, and carefully established GBOs can help with approaches that currently lack evidence. Although the fact remains that something that has been demonstrated to work for a presenting issue is typically more likely to work for that issue, than something that hasn't been demonstrated to work for that issue. Hopefully that is obvious – even though it appears to be a bit radical for the adoption sector generally.

Dr Tom Cawthorne is currently completing an NIHR Research Fellowship on how we can improve access to evidence-based support for care-experienced young people. Please email tom.cawthorne@kcl.ac.uk if you would like to find out more.

-

We would say those things are not mutually exclusive, so much as mutually interdependent. Effective support is best given when you know what the primary issues are, and especially when the family and young person have been fully consulted about what their most important goals are. At the moment there does seem to be the tendency of just giving people any available treatment rather than fitting the best treatment to the most important aspects of a young person's presentation. Working out what the best treatment is for the most important issues, involves doing an assessment and getting a collaborative agreement with the family - so that high quality individualised support arises from a good assessment.

Please contact info@cwclinic.com if you would like more information about our assessment and intervention packages.

-

A couple of comments mentioned overlaps been mental health and physical health conditions. That certainly happens and it makes sense for various reasons, including raising an issue of possible chromosomal issues (but of course there could be loads of other reasons too) as well as the potentially broad impact of early adversity on various bodily systems. It may be a physical health expert might not be the best professional to think about mental health, and vice versa and therefore that several types of professionals need to be involved - and need to be able to talk to each other effectively, which is often much easier said than done.

At the Child Wellbeing Clinic, we have a multidsincipnary team of psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses and dieticians. This includes several clinicians who have previously been based at Great Ormond Street Hospital and specialise in providing mental health support for young people within the context of physical health problems. Please contact info@cwclinic.com if you would like more information about our specialist support packages for young people with physical health problems.

-

That sounds very challenging and unfortunate. It is complicated for example, because we know co-occurring physical & mental health issues are likely, and that often means you need more than one type of assessment, possibly by different professionals [as above] and also need those assessments to be suited to questions being asked. Overall, the quality of assessments and their remit has been eroded by the unevidenced focus on only attachment & trauma in England and that may mean that families need to keep asking for further assessments as the ones previously provided don’t address the issues at all. And if you keep asking, which is appropriate if the previous assessments have been not fit for purpose, which if they were only about the minority issues of attachment and trauma, will often be the case, then of course, by trying to do what is right for your child you risk becoming a nuisance, and then the service attitude of blame comes into play [see blame above].

Against that, services may take an attitude of ‘stop looking and accept it as it is’ and that can sometimes be helpful, but sometimes it is not. Whatever else it ought to be agreed with the family and a shared view established of the benefits of that stance established, as well as a plan of what next.

-

Some of the off the shelf approaches we see offered to adopted children aren't tailored to the individual child but rather appear to be directed to all and any children, regardless of what their presenting issues are, and as such are not likely to be well suited to neurodivergent children and therefore risk being neurorepressive. This is can be especially true for approaches which are claimed to address early difficulties or sensory problems without an assessment that tailors the approached to fit young person and their specific needs.

More broadly, beyond adoption, there are concerns about some of the older style behavioural modification treatments, such as ABA [Applied Behaviour Analysis] and even its more modern form of Positive Behavioural Support [PBS] [link]. But there is a balance that needs to be struck between valuing neurodivergence as a valid part of neurodiversity, and recognising that it is hard to fit into a neurotypical world without some adjustments and if we assume the world is not going to suddenly become neuroaffirmative overnight, then there may be a role for helping to shape the kinds of responses that will enable a young person to have a more fulfilling life with their peers and in school and so face fewer challenges to their well-being. It is probably not a simple binary good/bad answer and depends a lot on what the treatment goals are and how they are implemented. ABA and PBS if delivered compassionately and collaboratively could be helpful for some autistic children and of course, the use of collaboratively agreed goals and the monitoring of these goals, helps ensure it is appropriate and that the young person stays in control.

-

We will do our next webinar on communicating about a young person’s needs with CAMHS and other stakeholders. Although there have been some exceptions here and there, access to CAMHS has rarely been great and this predated the establishment of the adoption support fund in England, but research about the impact of that fund in England has highlighted that inadvertently the fund may have made access to standard CAMHS services even harder [because families get told they can get services through that, rather than through statutory services]. And beyond England it seems likely that similar barriers have also increased given how much pressure statutory services are under.

One of the things we think acts as an inadvertent barrier is the existence of different narratives between parents, non-statutory mental health stakeholders and statutory services about what the issues are for adoption [and for care experienced children more generally]. These differences need to be explored, and parents probably need to be prepared to adjust the way they present their child's needs to fit with what services are able to offer. In an ideal world, services would be doing that extra work of accommodating different views collaboratively, rather than dumping it on families, but we are probably far from an ideal world in the current context, and perhaps if you want a particular outcome, it may well be you as the parent who has to do that work. This is not how it is supposed to be, but needs must?

-

The teenage years are definitely interesting, but actually so is the whole of childhood neurodevelopment, past the teenage years and well into the 20s [where we get a brief period of stability and then it starts going downhill, maybe around 35 to 40…]. The “chaos” of the teenage brain is sometimes overstated because in fact there is a huge amount of diversity and difference around different teenagers’ developmental trajectories and even children who are quite chaotic can often have periods of meaningful connection amidst longer or shorter episodes of dysregulation. We will do a webinar on the neurobiological legacies of early maltreatment and neglect, and as part of that we will present scientifically sound and helpful ways to think about neurodevelopment more broadly - definitely in opposition to simplistic ideas of “damage done” by early experiences and certainly distinct from the rather popular, but scientifically incoherent ideas about the triune brain, as if there were a basic reptilian brain overlaid through evolutionary processes of more sophisticated thinking… No, your brain is not like an onion with a tiny reptile inside, despite what so many popular, but frankly idiotic, “science” books say, and to be fair, even most psychology textbooks too, unfortunately [this is one of the best journal titles of all time, in a world leading and top ranking journal… [ link ]

A future webinar will cover the neurobiological legacies of early maltreatment and neglect and offer evidence-based ways to think about neurodevelopment- distinct from overly simplistic notions of permanent “damage”.

-

Yes, both Tom and Matt work with Rachel and colleagues [link], especially regarding the evidence-based approaches to assessment and treatment of care experienced and traumatised children and young people. But also with other experts, including Prof Robbie Duschinsky at Cambridge University on attachment [if you are interested in a definitive account of attachment theory and research, then see his phenomenal books on attachment theory and its developments, which are open access and free to download at Oxford University Press - [link]& [link] as well as on the quality of mental health services for children with social care contacts [link]. There is exciting work coming out that could hopefully course-correct the direction of travel for adopted children’s mental health support.

-

Absolutely, and the late Sir Michael Rutter and colleagues made this point explicitly in their publications. But we can still learn a lot about this ‘natural experiment’ not least about how even experiencing extremes of neglect, children showed a variety of different responses [early adversity predicts diversity of outcomes], even though more adversity tends to be worse on average despite this variation. But also that recovery happens and especially we learned a lot about the fundamental resilience of the attachment system in early life [people seem to forget this], along with the limits of recovery and resilience. [link]

A lot was learned about many different processes in these studies, but the one thing that we are lacking above all else in the UK is a high-quality epidemiological study of what the mental health needs of adopted children are. That has never been investigated, and it is a gaping hole in our knowledge of what we ought to be doing for families and how we can best support them. It means that the Department of Education has spent around half a billion pounds providing support in England, without knowing anything about what the issues are.

-

We are very sorry to hear that, and it is an all-too-common experience. However, it is even worse than it sounds because that knowledge has in fact been there all along, and we have known for more than 20 years about the kinds of issues that maltreated children are likely to present with, including elevated rates of neurodevelopmental problems and of comorbidities (Chaffin et al, 2005; Haugaard, 2004). Unfortunately, most services and commissioners haven't seemed to pick up on and implement that widely available research knowledge [by world leading experts in world leading journals!]. Instead, the adoption world in particular has often seemed to favour left-field, unevidenced-based accounts rather than the more traditional ones that follow the evidence closely, and that is an interesting thing in its own right.

We are currently involved in several research projects aiming to highlight this issue in the hope that it can change. We also recently wrote an article in the journal Adoption & Fostering on the risks of not recognising neurodevelopmental conditions in care-experienced young people, which we will upload to our website.

At the Child Wellbeing Clinic we also provide gold-standard neurodevelopmental assessment for autism and ADHD. Please contact info@cwclinic.com for further information.

-

We would broadly agree with that because it is consistent with what can be described as a “critical realist position” in the literature. You see that in practice to some extent as diagnoses keep changing every now and again in the different versions of the diagnostic manuals, as they get tweaked and refined when new research data accumulates or cultural values shift. So they aren’t ‘real’, so much as the current best shorthand for something and that is what makes them very useful.

It is quite possible to acknowledge that they aren't “real” but are still useful for communication and also for organising our thinking about the kinds of things that might have contributed to them occurring, what things might make them get worse and the kinds of things that might help them become less of an issue. So long as we keep an open mind about all the other things that might be going on and don't get fixated on them being fixed real things. That would be true for autism, as much as it is true for developmental trauma [which is not a diagnosis, strictly speaking] as it would be for foetal alcohol spectrum disorders or any other. We can use these categories, but we ought to keep in mind other possibilities as well as being aware of the limitations of their current definitions; because they are limited and they are likely to change. But that can be quite hard work, and you could end up, as a young person said to one of us the other day, “going down a philosophical rabbit hole about whether I really am autistic or not, with these conflicting ideas clashing inside my brain”. Perhaps it may be better not to over think these things?

Comments

Webinar Notes

Understanding Neurodevelopmental Conditions in Adopted and Fostered Young People

Introduction

Adopted and fostered children experience disproportionately high rates of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

This webinar explored the nature of these conditions, the complexities of diagnosis in care experienced populations, and the implications for support and intervention.

Neurodiversity and Neurodivergence

Neurodiversity refers to the natural variation in human brain functioning and associated behavioural traits. It challenges the assumption that there is a single “normal” neurological profile, recognising a spectrum of cognitive and behavioural differences as part of human diversity.

Neurodivergence describes instances where neurological functioning diverges sufficiently from the majority, the neurotypical profile, to be considered atypical. Examples include autism, ADHD, dyspraxia, tic disorders, and others.

Key points

Neurodevelopmental differences are dimensional, not categorical.

Boundaries between “typical” and “atypical” are often fuzzy.

Assigned diagnoses may vary across different assessments due to overlapping symptoms and lack of rigid cut offs, and also because being adopted or care experienced can draw the assessor away from the data and offer an easy alternative explanation, for example “attachment”.

A neurodiversity approach enables inclusion

People with autism often follow their own norms for eye contact, which may diverge from many social norms, see also cultural variations.

Look to others when talking, look away when listening, which frustrates some norms.

Possibly to concentrate on additional social communication task demands without distractions.

In any case, what is considered “appropriate” eye gaze is culturally varied. Direct eye gaze can be disrespectful in some contexts.

Adopting a framework that combines principles of neurodiversity and rigorous scientific methods is essential for reframing social cognition to include the strengths of autistic people and to create new definitions for understanding autism specific communication and interaction.

This will allow us to move beyond deficit based accounts of autism that have historically dominated the field of research, Fletcher Watson and Happé, 2019. Offering empirical support for the idea of difference, not deficit, will contribute to the progression of the rights of autistic people and will have important implications for practice and the public understanding of autism, Cage, Di Monaco, and Newell, 2019, p650.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD

Symptom clusters

Inattention

Hyperactivity and impulsivity

Combined presentation

Diagnostic features

Symptoms must be persistent, more than 6 months, present in multiple settings, and evident from early development.

Prevalence is about 5 percent in UK children, but much higher in children looked after, CLA, with some studies showing more than 50 percent.

Rates also differ across countries, typically higher in the US but lower in Scandinavia. Are these real differences or different approaches

ADHD assessment

Developmental history via caregiver interviews.

Reports from multiple settings, for example school.

Questionnaires, for example Conners, home, school, and self report, and neuropsychological testing can be very helpful but are usually not necessary.

Autism spectrum disorder, ASD

Diagnostic criteria, ICD 11 and DSM 5

Autism is characterised by

A Persistent difficulties with social communication and social interaction.

B Restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities.

All subtypes, for example Asperger’s and PDD NOS, are now classified under a single umbrella, Autism Spectrum Disorder. It is a unitary concept, varying in terms of severity and impact.

Terminology and identity

The preferred term is currently “autistic person”, but always ask individual preference.

Language reflects values, “difference, not deficit”, which aligns with neuroaffirmative principles.

Neuroaffirmative approaches

Celebrate strengths and diversity rather than framing autism as a disorder to fix.

Recognise that challenges often arise from societal inaccessibility rather than inherent pathology.

Neuroaffirmative approaches exist on a spectrum

Some reject all interventions for autism, locating the pathology in a society that needs to change for failing to embrace diversity fully.

Others accept that society ought to change, but in the meantime offer interventions collaboratively based on building strengths and identifying barriers to wellbeing for this individual and their family.

Adapt interventions collaboratively with the individual and family.

Autism assessments

Gold standard has at least two parts

Structured observation, ADOS 2, plus developmental interview, ADI R, 3Di, DISCO.

Multiple informants, for example parents and teachers, are essential.

Ideally, co occurring conditions, anxiety, ADHD, intellectual disability and daily living skills, should also be assessed.

A challenge for some adopted children and CLA is that there are areas of interest about language acquisition or delay and the emergence of social reciprocity, imagination and play that normally occur between 2 to 5 years. Easier if this history is available, but not impossible even so.

Prevalence of autism

Prevalence is about 1 percent nationally but almost 3 percent in 10 to 14 year olds, and rising

Is autism overdiagnosed, Fombonne, 2023

“At a population level, the unjustified use of intensive services raises concerns about equity and fairness in services access for children who have neurodevelopmental disorders other than autism and struggle to access support services that they need as much as their peers with ASD.” p713

“The complexities, costs, and resources involved in diagnostic confirmation are considerable, justifying the calls for streamlined diagnostic procedures in clinical settings and rapid phenotyping in large scale studies. Yet, while lighter instrumentation and a compressed diagnostic evaluation or confirmation process may be needed, or indeed be the only available option, investigators should keep in mind the risk of overdiagnosis of ASD and devise measurement strategies that limit misclassification and false positives.” p713

Is a two day ADOS training sufficient to make a tester also an effective diagnostician

The neurodivergent spectrum and assessment

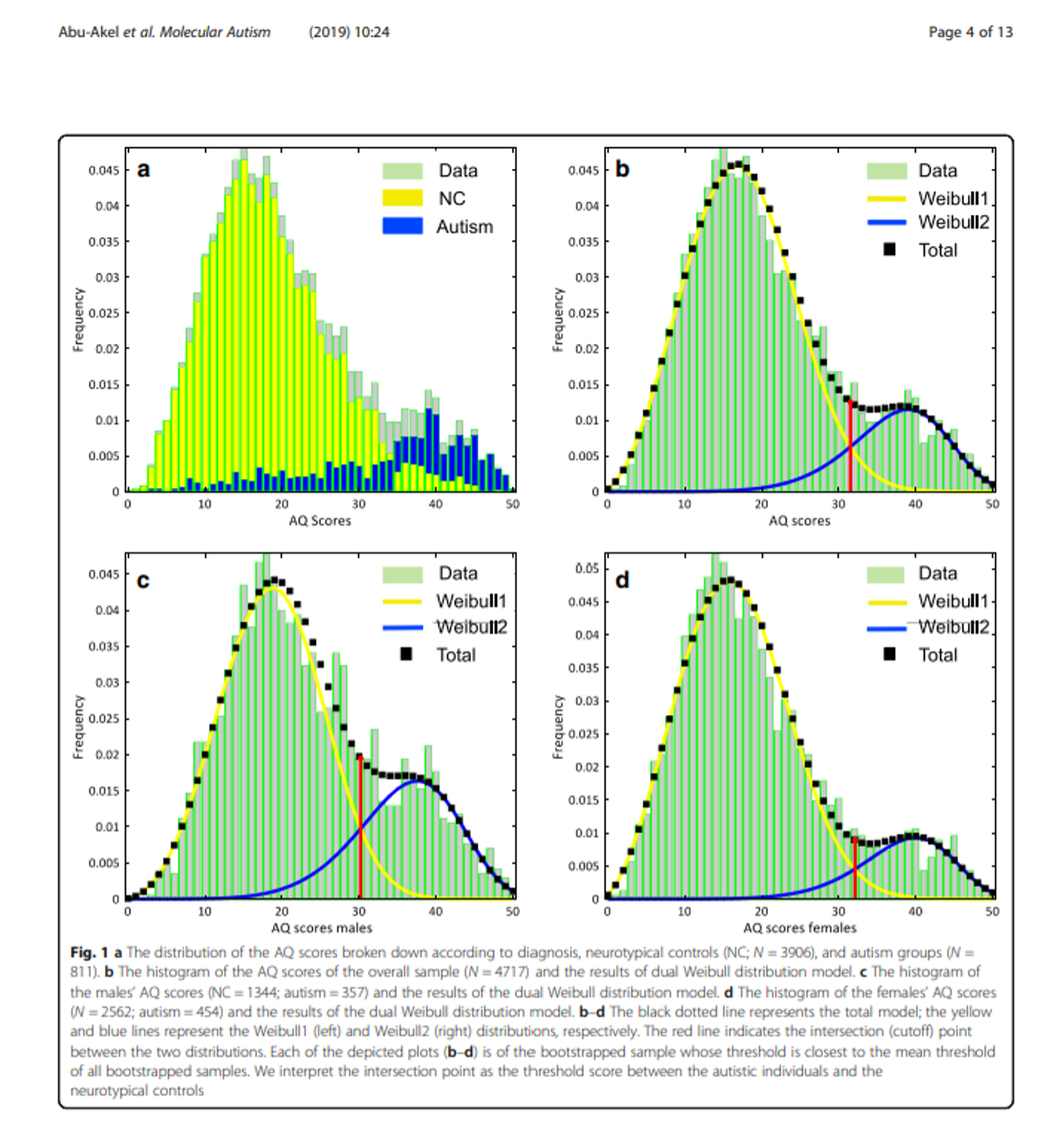

Using the example of autism, but similar ideas for ADHD too, the distribution of symptoms is on a continuum or spectrum, rather than a sudden step change from diagnosis absent to diagnosis present.

The spectrum is unlikely to be a perfectly symmetrical bell curve. The study below is an example of one way of mapping symptoms.

The distribution of symptoms here is heavily skewed towards the neurotypical end, to the left, with a bimodal distribution, a bump to the right, and it also looks different for males and females.

So when we are making a diagnostic decision as to whether someone meets or does not meet criteria, the boundaries, red lines, are not fixed and could be a bit fuzzy.

Diagnostic diversity, fuzziness

The graphs above show that there can be a fuzzy area in which neurodiversity becomes divergent or atypical which leads to diagnosis.

The fuzzy area is real and inevitable because of neurodiversity.

There is not a hard and fast cut off for some children and young people.

Some adopted young people in the fuzzy area get assigned to different bins, categories, labels, diagnoses, in different assessments.

First assessment equals autism, second equals ADHD, third neither, attachment and trauma.

There is often high comorbidity with other neurodevelopmental and non neurodevelopmental conditions, which can further blur the picture.

Autism

Lai et al, 2019

ADHD, 28 percent

Anxiety disorders, 20 percent

Sleep wake disorders, 13 percent

Disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders, 12 percent

Depressive disorders, 11 percent

Obsessive compulsive disorder, 9 percent

Bipolar disorders, 5 percent

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 4 percent

Seventy percent have at least one co occurring disorder, 41 percent have two or more. Anxiety, 42 percent, ADHD, 28.2 percent, and behavioural disorders, 30 percent, were most common, Simonoff et al, 2008.

ADHD

Njardvik et al, 2025

Oppositional defiant disorder, 34.7 percent

Behavioural disorders, 30.7 percent

Anxiety disorders, 18.4 percent

Specific phobias, 11.0 percent

Enuresis, 10.8 percent

Conduct disorder, 10.7 percent

Larson et al, 2011, 33 to 52 percent have one co occurring condition, 16 to 26 percent have two or more.

For adoptive children especially, there is an easy alternative, false, account of attachment or trauma instead of extra, comprehensive assessment.

Neurodivergence assessment and adoption

Recent conversation with a clinician about an adopted child

I did ADOS and ADI, and it was not autism but more of an attachment issue.

What was the evidence for attachment pathology

Well, it was not autism, that is, no evidence of attachment problem.

If not clearly autism, then if adversity present, trauma or attachment

Is it hard to diagnose autism in maltreated children

It can be, mainly because of the lack of early developmental history, but in over 20 years never because of a confound with attachment problems or trauma.

If you know about autism, ADHD, and attachment or trauma, and the evidence base, then it can be straightforward.

Like following a recipe, but you do need to know the ingredients.

Complexities in adoption and foster care

Both autism and ADHD are highly heritable, so birth parents may share some of the phenotype, the condition and its broader symptoms.

Autism heritability, 64 to 91 percent.

ADHD heritability, 22 to 80 percent.

The condition may be only partially expressed in a birth parent and not diagnosed, or fully expressed and services have not diagnosed them due to systemic biases, but still a heritable risk.

Many individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions make excellent parents.

But there are higher rates of parental mental health problems, substance misuse, domestic violence, in utero toxin exposure, and challenges engaging with services.

This is probably also related to shared genetic vulnerabilities with parental mental health difficulties, substance misuse, and trauma exposure, not just experience.

Complex bidirectional relationships between genes and experiences

Individuals with autism and ADHD are more likely to experience traumatic events compared to their neurotypical peers, due to social vulnerabilities and impulsivity.

After exposure to trauma, children with autism and ADHD are more likely to develop PTSD than their neurotypical peers, Haruvi Lamdan et al, 2018.

Children who have been abused and neglected are more likely to have symptoms of heritable neurodevelopmental conditions due to shared genetic factors, rather than the abuse or neglect causing the neurodevelopmental conditions, Minnis, 2024.

Children who are abused or neglected and have neurodevelopmental conditions are twice as likely to develop serious mental illness in adolescence.

There is some evidence from prospective studies of structural and functional brain changes following trauma exposure, Scheeringa, 2024.

There is more evidence of underlying brain differences in those who do or do not experience trauma and later develop PTSD.

Missed diagnoses, including comorbidities, co occurring issues, are a huge problem for these children.

Trauma, adversity, and misdiagnosis

Trauma versus neurodevelopmental conditions

Trauma does not change the core presentation of autism. If it looks like autism, it probably still is autism.

Overlap in soft signs can cause confusion, but these are often non specific and not diagnostic.

Several attractive graphics show overlap between ADHD and trauma, or autism and attachment, that have no basis in science or evidence.

The picture above does not pit core symptoms against each other but rather non specific soft signs which are not used to make the diagnoses. This is therefore meaningless, see also the Coventry Grid.

If a clinician chooses to use over inclusive and invalid definitions of problems, then they have chosen to increase the chances of overlap and confusion.

If a clinician is clear what each disorder is, how they differ, and how they overlap if at all, then diagnosis is much easier and more reliable, diagnostician versus tester.

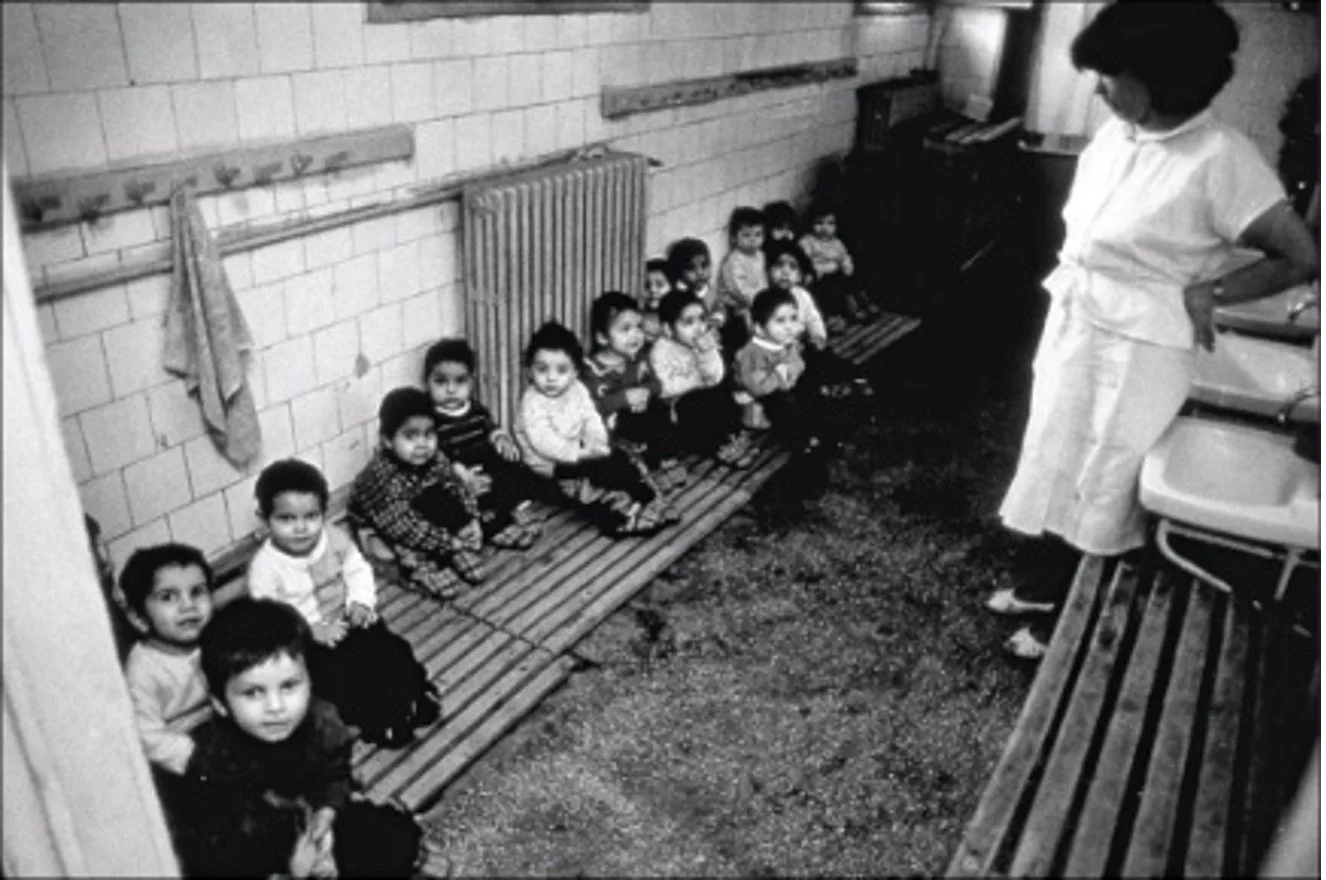

Romanian adoption studies

https colon slash slash www dot kcl dot ac dot uk slash research slash the english and romanian adoptee era project

Profound deprivation led to some cases of quasi autism with atypical patterns, more social approach, symptom improvement over time, equal gender ratio.

There were also issues with inattention and overactivity, and some specific attachment issues, we will do another webinar to think about these issues more broadly.

The range of issues was combined into the concept of Deprivation Specific Psychological patterns, DSP, meaning broad developmental impacts from extreme neglect.

Most adopted children, even from severe deprivation, did not develop autism and most, but not all, showed remarkable recovery.

Diversity is the norm after early adversity

Even with very similar early experiences, the orphans outcomes did not converge onto the same issues but were wide ranging and non specific, that is, not one or two things like attachment or trauma.

“It has come to be generally accepted that the psychopathological effects of psychosocial stress and adversity are diagnostically nonspecific.” Kumsta et al, 2010.

“The presence of multiple neurodevelopmental and mental health problems, with characteristic developmental trajectories, creates a distinctive, complex, and heterogeneous clinical picture. Any two affected children rarely presented with the same clinical profile over time.” p1545.

Most adopted children, even from severe deprivation, did not develop autism and most, but not all, showed remarkable recovery.

Challenges experienced by adopted and fostered children with neurodevelopmental conditions

Elevated risk of traumatic events

More likely to develop PTSD following traumatic exposure

Challenges around transition and change in routine

Sleep difficulties are a risk factor for anxiety and depression, PTSD

Bullying and social exclusion

Stigma and social identity issues, camouflaging

Delayed diagnosis

Sensory challenges

Change in caregivers, harder to develop relationships, need caregivers with understanding of the individual profile

Support and adaptation strategies

Autism

“If you have met one autistic person, you have met one autistic person”, a person cannot know that type.

Individualised assessment to identify drivers of distress, for example anxiety and sensory needs.

A child will have a pattern of strengths and needs to build on.

Autistic siblings may have very different needs, which is especially challenging.

Environmental adaptation, for example reducing sensory overload and providing structure.

Skills development consistent with personal goals.

Avoid therapies that make unrealistic social or emotional demands, some of which are especially popular as off the shelf adoption therapies, and which do not adequately take into account social communication challenges.

ADHD

First line, environmental adaptations at home and school, whether or not medicines are also used.

Keep instructions short, give frequent and specific praise, use novelty, support gradual executive skill development.

Medicines can be very helpful for moderate to severe ADHD symptoms, but require careful titration and monitoring, as well as consideration of effects on comorbidities.

Pathological demand avoidance, PDA

Describes extreme avoidance of everyday demands, potentially due to anxiety, cognitive rigidity, or poor environmental adaptation.

“The term demand signifies a pressure or expectation from the child’s environment, either personal or physical, or it can refer to the child’s perception of external expectations pressuring them to do something different from what they were thinking or doing. The term avoidance signifies a behavioural response to this demand.” Newsom et al, 2003.

Not recognised as a distinct diagnostic category. Behaviours likely arise from multiple pathways.

For some clinicians and families, the pathological demand avoidance concept is helpful for making sense of complex developmental presentations. But there is not yet good evidence that this is a distinct group, no discriminant or predictive validity.

Pathological demand avoidance, symptoms but not a syndrome, Green et al, 2018. This means it is an important and meaningful part of the formulation, but not necessarily helpful to consider as a thing in itself.

Associated with different processes

Anxiety

Cognitive rigidity, and related intolerance of uncertainty

Limited prosocial emotions

Differences in theory of mind

Lack of effective environmental adaptations

Oppositional defiant disorder, plus irritability

There are risks of harm if this is framed as a deficit solely within the child.

Key takeaways

Neurodevelopmental conditions in adopted and fostered children are often underdiagnosed or misattributed to trauma or attachment difficulties.

Autism and ADHD are highly heritable, and adversity interacts with, but does not cause, these conditions.

Therefore birth parent mental health issues are very relevant. It is not all experience.

Accurate, multi informant assessment is critical for appropriate support.

Neuroaffirmative approaches focus on adaptation and inclusion, not fixing differences.

Co occurring conditions are common and should be actively assessed and managed.

What Next?

Thank you for joining our webinar and for all of your thoughtful questions and contributions to the discussion.

We hope you found the session useful and that it has given you new insights into understanding and supporting adopted and fostered children with neurodevelopmental conditions.

If you would like to find out more about our services or book an appointment, please follow the links below.